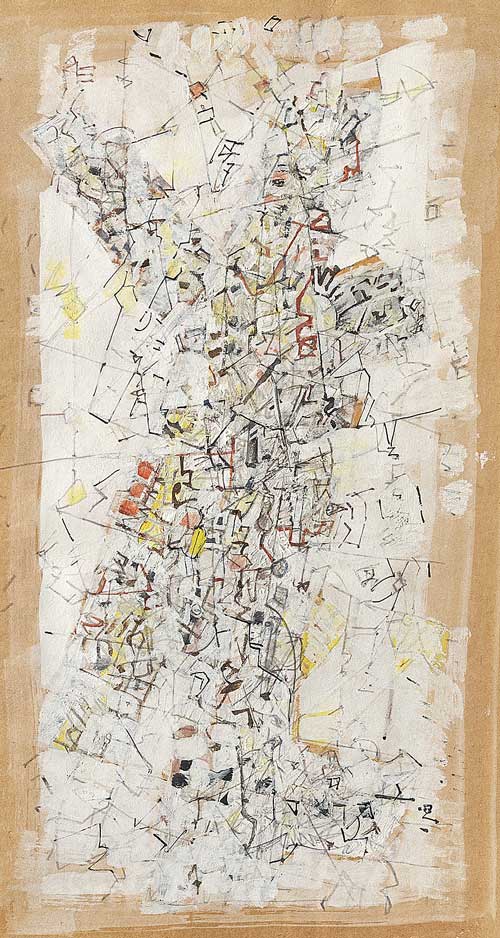

Mark TOBEY World, 1960, tempera on paper, 12.5 x 17 cm

Courtesy Jeanne Bucher Jaeger, Paris ©Jean-Louis LosiMARK TOBEY

TOBEY or not to be ?october 16, 2020 - January 16, 2021

Opening Thursday, October 15, 6 pm - 8.30 pm

Jeanne Bucher Jaeger | Paris, MaraisEvents during the exhibition :

Saturday, November 14, 6 pm : The Bach Project

East meets West with Raphaëlle Moreau, violin and

Madjid Khaladj, Iranian Percussion

Thursday, December 10, 6.30 pm

Screening of the film Mark Tobey by Robert Gardner (1952) (19 min)

Thomas Schlesser: Tobey by the way

Patrick Chemla, violinist: John Cage, 4:33

I have discovered many a universe on paving stones and tree barks. I know very little about what is generally called "abstract" painting. Pure abstraction would mean a type of paiting completely unrelated to life, wich is unacceptable to me. I have sought to make my painting "whole" but to attain this I have used a whirling mass. I take up no definite position.

Maybe this explains someone’s remark while looking at one of my paintings: "Where is the centre?"Letter from Mark Tobey (February 1, 1955), exhibition catalogue, Musée des Arts décoratifs, 1961

|

| MARK TOBEY Space Rose,1959, tempera on paper, 40 x 30 cm Courtesy Jeanne Bucher Jaeger, Paris © Jean-Louis Losi |

A HISTORICAL EXHIBITION |

|

On the occasion of the 130th anniversary of the birth of Mark Tobey (1890 - 1976), the exhibition offers a convergence of perspectives: that of the the Galerie Jeanne Bucher Jaeger, the artist's In addition to the previous 2010 retrospective organized at the gallery by Véronique Jaeger to celebrate the 120th anniversary of the artist’s birth, as well as the continuous presentations the gallery has regularly organized throughout the years, the gallery recently contributed, through the loan of works, to the important retrospective Mark Tobey: Threading Light (curated by Debra Bricker Balken) at the Peggy Guggenheim Collection in Venice and the Addison Gallery of American Art in Andover in 2017-2018, as well as to his 2018 solo exhibition at the Pace Gallery in New York. This non-commercial solo exhibition presents some forty essential works by the artist spanning thirty years of creative activity, from 1940 to 1970. There hasn’t been a solo exhibition of his works in a French Museum since the 1961 exhibition at the Musée des Arts décoratifs in Paris, nearly 60 years ago. The exhibition is scheduled to travel in Europe, first to Lisbon in 2021, then to Venice in 2022. |

|

Tobey’s international reputation grew, during his lifetime, mainly in Europe, where he had his first solo exhibition at the Jeanne Bucher Gallery in 1955. His work was shown in London in the Tate Gallery 1956 exhibition American Painting, alongside works by Kline, De Kooning, Motherwell, Pollock, Rothko and Clyfford Still. He was the second American, after Whistler, to win the Grand Prize of the Venice Biennale in 1958. His first exhibition in a French institution was at the Musée des Arts décoratifs in Paris in 1961. His settling in Basel in the early 1960s was facilitated by the active support of Ernst Beyeler. Mark Tobey was the subject of a retrospective at the New York MoMA in 1962, and again in 1976. This discrete artist, nicknamed “the wise man of Seattle,“ was imperceptibly and progressively surrounded by an exceptional aura, that of a founder of modernity, of a mystical artist, but also of a philosopher of abstraction whose works are rare, intimate, dense, and deep. (Cécile Debray) His works are now part of the collections of many prestigious international institutions, such as the Mnam / Cci Centre Pompidou in Paris, the Fondation Beyeler and the Kunstmuseum in Basel, the Guggenheim, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Museum of Modern Art, and Whitney Museum in New York, the Addison Gallery of American Art in Andover, Massachusetts, The Art Institute of Chicago, and the Tate London ... |

|

The title TOBEY or not to be ? refers to Mark Tobey’s English roots, through the voice of Shakespeare, to his existential quest, to his own questioning linked to his artistic, philosophical and spiritual approach; it also emphasizes Tobey’s continued importance today by embodying the "to be". To be. What is To Be in the contemporary era? |

THE EXHIBITION CATALOGUE |

|

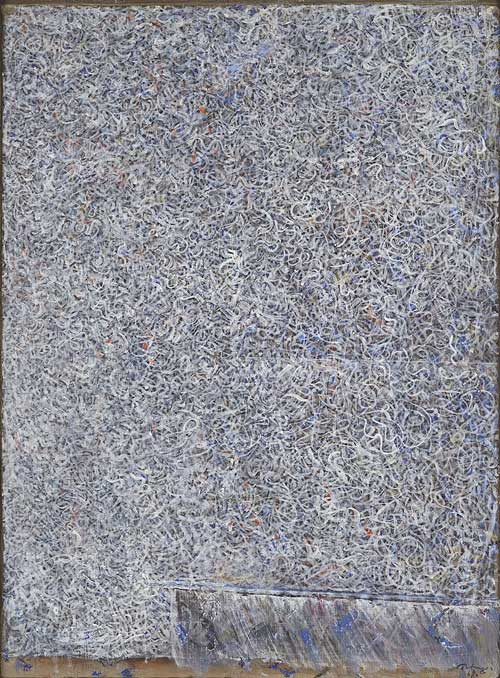

| MARK TOBEY Jazz Singer,1954 gouache, ink and pencil on paper, 45.1 x 29.5 cm Courtesy Collection de Bueil & Ract-Madoux, Paris |

|

On the occasion of this exhibition a catalogue has been published by Gallimard with contributions by Laurence Bertrand Dorléac, Cécile Debray, Dr. David Anfam, Etienne Klein, Stéphane Lambert and Thomas Schlesser. • Laurence Bertrand Dorléac: historian, art historian, professor at Sciences Po (Paris), specialist in artistic production in France during World War II (1938-1947) and in particular during the |

|

This catalogue also contains texts by : Janet Flanner, Tobey, L’OEil, 1955 Dore Ashton, Mark Tobey et la rondeur parfaite, Revue XXème François Mathey, text from the catalogue of the Mark Tobey exhibition Françoise Choay, Mark Tobey, Peintres d’aujourd’hui, 1961 Jean-François Jaeger, Introductory text of the TOBEY catalogue, |

THE PARTICIPANTS IN THE PROJECT |

|

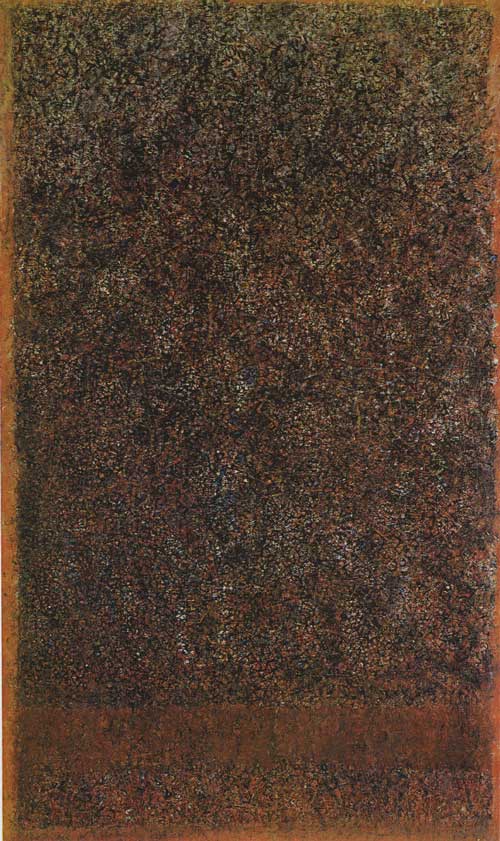

| MARK TOBEY Unknown Journey, 1966, oil on canvas, 207 x 128 cm, © Adagp, Paris Location : Paris, Centre Pompidou - Musée national d’art moderne - Centre de création industrielle Photo © Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / image Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI |

|

Since its creation by Jeanne Bucher in 1925, the Galerie Jeanne Bucher Jaeger has always initiated and nurtured close and privileged relationships with artists, institutions and private collections. Considered today as an institution that has exhibited the great European and international artists of the 20th century, and now a leading exponent of the 21st century, the gallery was featured in 2019-2020 by the Mnam / Cci Centre Pompidou in the Museum’s new display of its modern collections. Tobey’s Animal Totem was shown aside works by Giacometti, Kandinsky, Staël, Ernst, and Vieira da Silva ... It was in 1945, during her second trip to the United States, that Jeanne Bucher met Mark Tobey, whose work was presented at the Willard Gallery in New York. Jeanne Bucher came back with works by Tobey, whom she wanted to show in France, but she succumbed to illness in 1946, and it was Jean-François Jaeger, her successor, who in collaboration with the New York gallery, organized the artist’s first exhibition in Europe ten years later. After winning the Grand Prize for Painting at the 5th Venice Biennial in 1958, and following his second exhibition at the gallery, Tobey’s work was shown at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in the 1960 exhibition Antagonismes (curated by François Mathey, museum curator from 1953 to 1985, and Julien Alvard, art critic). The curators sought to understand contemporary painting through Harold Rosenberg’s approach (gestural abstraction) and through a reading of Nietzsche, and proposed major typologies. Tobey, in the section «Nature, Landscape,” was presented as a descendant of Monet, Redon, and Whistler, alongside Rothko and the younger artists, Sam Francis and Bryen (Cécile Debray). The following year, in 1961, the Musée des Arts Décoratifs organized the first retrospective of his work in France. |

|

Two new exhibitions, in 1965 and in May 1968 - during which visitors from the Latin Quarter, sprayed with tear gas, took refuge in tears in the rue de Seine gallery -, were milestones in Mark Tobey’s tenure at the gallery. Following this latter exhibition the Musée National d’Art Moderne acquired Unkown Journey (1966), one of the artist’s very few paintings owned by a French institution, that the Mnam / Cci Centre Pompidou is lending to the gallery for the occasion. "Everything, in its true amplitude, expresses the truth of a prostrated waiting, a breathing in perfect tune with meditation. Can the intensity of an emotion or a need for communication be framed by anything other than the mastery of an adequate, traditional or almost organically secreted language in order to manifest a state of consciousness? He who, for a long time, turned his mind from Seattle to China and Japan knew how to take the path of meditation and open the initiatory passages to the breath. No gesture could express the extreme of sensation, so precious in its advent that a lack of interpretation would destroy it. It is necessary to know how to earn the transfer of the impulses of the soul into tempera through a disinterested listening, without getting involved in any prestigious competition, in the austere solitude of the studio,“ as Jean-François Jaeger would write about Tobey in the catalogue Dialogues with fellow travelers, May 30 - July 8, 2000. Mark Tobey also embodies the spirit of the Jeanne Bucher Jaeger Gallery, with its particular focus on the East, and spirituality. In the matte temperas - his favorite medium - his measured and musical language elaborates a cosmic space in whirlwinds of transcendental meditation. The modesty of its format unfolds its spiritual dimension unto infinity. |

|

| MARK TOBEY White Space,1955, tempera on paper, 20.5 x 31.5 cm Collection Particulière. Courtesy Jeanne Bucher Jaeger, Paris ©Jean-Louis Losi |

|

The Collection de Bueil & Ract-Madoux was created in 2016 by pooling the respective collections of Jean-Gabriel de Bueil and Stanislas Ract-Madoux. This collection of pictorial works covers Open to working with institutions, the Collection de Bueil & Ract-Madoux has participated, through the loan of some sixty works, in some forty exhibitions both in France and abroad. Its aim is to promote a convergence of perspectives sparked by a synergy between different contributors in the promotion of an artist and their work. By participating in this innovative and non-commercial project with the artist’s historical gallery in Europe and with the Mnam/ Cci Centre Pompidou, the Collection de Bueil & Ract-Madoux |

MARK TOBEY |

|

Born in Centerville (Wisconsin) in 1890, a year after Van Gogh’s death, Mark Tobey said he had a wonderful childhood: nature, no culture, few books and the word “art” absent from hisvocabulary. In winter, when the temperature dropped below freezing, he would skate on the frozen river; in summer he would fish and swim. Native Americans had inhabited the area and used the local red stone to carve the peace pipes which they solemnly smoked in their assemblies. (Janet Flanner) Trained in the 1910s at the Art Institute of Chicago, he visited the Armory Show in 1913 and was struck by Marcel Duchamp’s Nu descendant l’escalier, which appeared to him to be a sort of crucifixion, and of which he made a variation in 1947 entitled The Deposition. In 1918 Tobey converted to the Baha’i faith which celebrates the harmony that reigns between humanity and the whole of nature. |

|

| MARK TOBEY Escape from Static,1968, tempera on paper, laid down on panel, 67 x 48.5 cm Courtesy Jeanne Bucher Jaeger, Paris ©Jean-Louis Losi |

|

Defining himself as neither abstract not figurative, Tobey had an intimate experience of Cubism in the 1920s, when he was making a self-portrait in his studio. As he was observing the light from the ceiling, he had a sudden vision: let’s imagine I’m a fly. I can go to the easel, go in any direction, at any time, walk on the walls, and so on.... In this closed universe, I fed on the circuit defined by the fly: no more frame, no more Renaissance. In 1922 he joined forces with Teng K’wei, who trained him in calligraphy. Upon his return in 1935, his White Writings were born. Still teaching at the famous Dartington Hall School in England, where he would spend 7 years, Tobey began to paint his calligraphies in white: Crystalline Forms, Out of Space, and Night Rising are titles borrowed from natural processes to designate paintings that attempt to represent these very processes. (...) What he wants to paint is a balance between space and matter. (...) He treats form as integrated with movement. (Janet Flanner) |

|

| MARK TOBEY Animal Totem,1944, tempera on cardboard, 37 x 17,5 cm Courtesy Jeanne Bucher Jaeger, Paris ©Jean-Louis Losi |

|

It was Tobey’s combination of the “field” and “writing” that renders him a forerunner to recent and contemporary art. Donald Judd’s Minimalism with its limited/limitless planes, Cy Twombly’s scripts, Brice Marden’s fertile encounters with Eastern art and culture, Robert Ryman’s lengthy romance with white, Zeng Fanzhi’s painstaking pigment filaments and Ellen Gallagher’s crafty transformation of the pictorial field into a “cosmology of signs” that critique race and other contested issues… the list could continue apace.“ David Anfam, Intimate Immensities. From then on, the work of the man nicknamed "the mystic of the Northwest" or "the wise man of Seattle" gained national and international recognition. Homosexual, he fled the McCarthyism of his native country in the mid-1950s and found, in Paris then Basel (where he spent the last 15 years of his life), the climate conducive to his aspirations. After exhibitions at the Whitney Museum in New York in 1951 and the Musée des Arts décoratifs in 1961, retrospectives of his work were organized, notably at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1962 and at the National Gallery of Art in Washington in 1974. Tobey has thus, throughout his life, both assimilated and lavished an extraordinarily sharpened sensibility on the continuous animation constituting the fabric of the world, its "breath-energy", that is to say the Chinese qi. From 1935 onwards, the way he treated the city, by abandoning the architectural foundation and the diktat of massiveness in favor of rhizomatic lineaments, swirling crumbles that seem both to disperse and to magnetize each other, stemmed from a perception attuned to the conduits of energy, to the tiny infinite transitions specific to the concepts For him the cities on the Pacific coast were gateways to the Eastern world. In Seattle, didn’t he realize how close he was to the East? In the solitude of a Zen cloister in Kyoto, did he not realize how much he had remained a man of the West? There is as much of the East, Africa, Oceania and Prehistory as there is of the Far East in Mark Tobey’s works. Around 1940, forms became simplified (...) In his Animal Totem (1944), animals hook themselves to a tree like this Oceanian samba hook, where birds give life to the spirit of the ancestors. As for the trunk, it deserves to enter into a dialogue with one of those wooden statues of the middle Sepik which, among the Papuans, represent a skeletonized human body - the edges are the ribs, the center the heart; that is the cost of making the ancestor present. (Laurence Bertrand Dorléac) After the crowd of humans, Tobey explores the crowd of rocks, of lichens, of stars. From the infinitely small to the limits of the universe, his gaze questions a culture of microbes and the celestial vault with equal passion. Faced with the opposition of the same and the other, of the particular and the general, in the face of the enigma of the limit, Tobey rediscovers the astonishment of the thinkers of ancient Greece. The fact that A differs from B is for him so little part of eternal truth that he will come back to this astounding fact ceaselessly. It is through the renewed freshness of this questioning that Tobey takes his historical place within our time, the one where Heidegger, Beckett, and Wols suddenly logically question the logical foundations of Western humanism. (Françoise Choay) The Sumi series of 1957, including Composition N° 1, produced in the usual method of calligraphy by dipping bamboo brushes in Indian ink,was born in a moment of crisis for Tobey. His friend Lyonel Feininger died in January 1956. Their black and white fury, their bright speckling, their breaks and curves, are clearly suggestive of a "wild order" (...) (Thomas Schlesser). Tobey evokes them "like a kind of fever, like the earth in spring, or a hurricane". (Cécile Debray). |

|

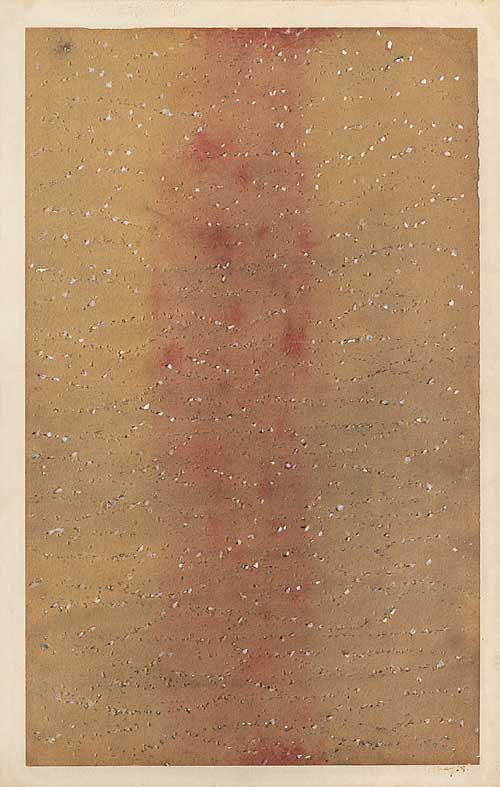

| MARK TOBEY Pierced Space, 1959, tempera and incisions on cardboard laid down on cardboard, 46,50 x 30 cm Courtesy Collection de Bueil & Ract-Madoux, Paris |

|

In Pierced Space (1959) a multitude of dots revealing the violence of the world can still be found: the material is delicately incised and the bloody shadow that crosses it from top to bottom reaches us like the abbreviation of a bruised body with red stains. It is reminiscent of the anthropomorphic Mbole face mask from Central Africa. The human is never far away. What Tobey engages with in this form, which is more or less clearly distinguishable from the image, has to do with the «image in the carpet,“ the one we are always looking for, because it contains the enigma of every apparition. Even the very abstract World contains its shadows behind the tight white interlacing. In his tempera on paper Within Itself (1959), one seems to perceive in the magma of threads a very light form in the center left. (Laurence Bertrand Dorléac) A writing board. White, black, purple, grey, and brownish signs lie one on top of the other, one inside the other, on a light pink background. A dense, impenetrable, unified, vibrant surface; but as is often the case with Tobey, how much depth, how much space it suggests! The gaze tries in vain to penetrate it, to pierce it through to the light; it continues to sink into the bushes, becomes entangled, cannot escape. And the longer it remains there, the greater the secret becomes. Everything comes back into itself, remains imprisoned within itself. (Wieland Schmied, Tobey, Éditions Pierre Tisné, 1966) |

|

| MARK TOBEY Within itself, 1959 tempera on paper, 20,3 × 28,8 cm Courtesy Jeanne Bucher Jaeger, Paris |

|

Until his death in 1976 in Basel at the age of 85, Tobey, gifted with a keen sense of observation, never ceased to travel the world, and the worlds, contemplating Nature and the Universe in their infinite variations. John Cage said of his friend: For him everything was alive. Constantly on the move - the ancient Greek philosophers held this to be essential to the soul - Mark Tobey said he was trying to remove from the cosmos a few fragments of the beauty that life contained in innumerable qualities. In the current period of mutation that humanity is going through, doesn’t Mark Tobey’s work, nourished by cosmic intuition and the unity of Man and the Universe, make even more sense? |

| It is a bit what I understand from what you’re telling me about Tobey’s holism, which itself reminds me of Plotinus’s philosophy, in which any entity draws its consistency not in the fact that it is, that it “possesses being,“ but in the fact that it is “one and unified“: it is the unity of the thing that articulates its different parts and that assures its being, without which it would disarticulated. Etienne Klein, Tobey entre art et science, interview with Thomas Schlesser. |

ANNEX - TEXTS |

|

Text by François Mathey, Mark Tobey exhibition, Musée des Arts décoratifs, 1961 Because of the imponderables whose vaguenesses surround Tobey’s figure like a halo, he is readily identified with an esoteric world where Zen and mysticism, Lao Tzu and Saint John of the Cross are all happily mixed together (...) There is some indiscretion and shamelessness in using such perilous and charged qualifiers as “mystic”, “painter of the depths.” and “witness of the invisible worlds" when speaking of an artist. Every work must be approached with consideration, and the more secretive its language appears, the more attention it requires. Tobey says: "One dies alone, one does not communicate, but the fact that the inexpressible escapes definition does not mean that it lies beyond the limits of human beings. Following his conversion to the Baha'i faith, Tobey left New York in 1922 to experience the solitude of the northwest coast, where he intended to start all over again. The Baha'i Faith teaches that man will gradually come to understand the unity of the world, that the prophets are all one, and that science and religion are the two forces of attraction that lead the universe. Trips to the Sinai, Europe, and Shanghai, a retreat at the Zen monastery of Kyoto, return trips to Seattle and Europe, stays in Paris and Basel, music, "white writing," calligraphy, sumis and prints— these are the stages and paths of his dialogue between the visible and the invisible, space and time, the moving quest for a transcendental truth. Through the network of his |

|

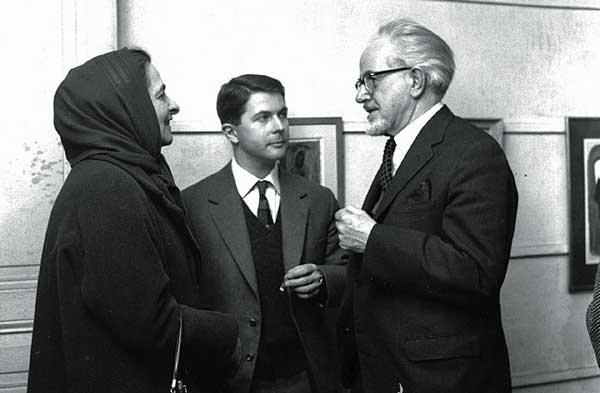

| Mark Tobey, François Mathey and Darthea Speyer Galerie Jeanne Bucher, Paris 1959 |

|

Text by Jean-François Jaeger, exhibition MARK TOBEY, 1968, Jeanne Bucher gallery It is not for us to do an exegesis of Mark Tobey's painting, but to show some significant works into which anyone can dive, as we do ourselves, to the level one is capable of reaching, accepting the risk of vertigo with the payoff of enchantment. The multiple splendors offered to the mind are unique in their revelation. The benefits of the artist's experimentation with transcendental reality can only be communicated through suggesting a particular quality of order, light, space, activity, and balance in the pulse. At the level of the work, this knowledge, which has become organic and is thus subject to its own laws, is delivered for us to consume. Its effectiveness lies less in the surprise effect it provokes, blunted as soon as it appears, than in its power to catalyse, condition or accelerate the mind of the spectator defied to participate. Mark Tobey's painting appears to us as an invitation to a journey into a sphere of vague dimensions, whose moving structures offer a point of reference only to be immediately transformed, according to a moment which, as it develops, becomes more and more coherent, more and more constructive, until it provides a fundamental sense of immutability. Yet Tobey’s painting remains uncomfortable to the extent that all the contemplator’s concepts are meshed, then untied and harmonized along the particular organization of Tobey’s universe. When, fifty years ago exactly, Tobey found in the Baha’i philosophy the answer to his need for universality, he didn’t yet know that he would find there the principle of synthesis between two tendencies that animated him: respect of the cultural traditions of the West and attraction to the mysticism of the far East. The confluence of these apparently contradictory trends took place much later, far from fads and their turmoils, in the Basler no man’s land. At the height of his course, the solitary artist engages himself in the faithful transcription of inner states without worrying about rhetorics anymore, supposing that Mark Tobey ever cared for any values other than spiritual ones. Maria Helena Vieira da Silva, Jean-François Jaeger and Mark Tobey, Galerie Jeanne Bucher, Paris 1959 |

|

| Maria Helena Vieira da Silva, Jean-François Jaeger and Mark Tobey, Galerie Jeanne Bucher, Paris 1959 |

|

Exposition du 16 octobre 2020 au 16 janvier 2021 Jeanne Bucher Jaeger | Marais, 5 rue de Saintonge 75003 Paris www.jeannebucherjaeger.com - info(at)jeannebucherjaeger.com - +33 (0) 1 42 72 60 42 |