MOMA TO PRESENT MORE THAN 100 WORKS BY 50 WOMEN ARTISTS

EXPLORING INTERNATIONAL ABSTRACTION IN THE POSTWAR ERAThe Exhibition Features Nearly 40 Recent Acquisitions—Drawings, Paintings,

Photographs, Prints, Sculpture, and Textiles—and Other Landmark Works from the

Museum Collection, Many on View for the First Time at MoMAMaking Space: Women Artists and Postwar Abstraction

April 15–August 13, 2017 Floor three, Exhibition Galleries

NEW YORK, The Museum of Modern Art presents a major exhibition surveying the abstract practices of women artists between the end of World War II and the onset of the Feminist movement in the late 1960s. On view from April 15 through August 13, 2017, Making Space: Women Artists and Postwar Abstraction features approximately 100 works in a diverse range of mediums by more than 50 international artists. By bringing these works together, the exhibition spotlights the stunning achievements of women artists during a pivotal period in art history. Drawn entirely from the Museum’s collection, Making Space includes works that were acquired soon after they were made in the 1950s and 1960s, as well as many recent acquisitions—including a suite of photographs (c. 1950) by Gertrudes Altschul (Brazilian, born Germany. 1904–1962), an untitled sculpture (c.1955) by Ruth Asawa (American, 1926-2013), and an untitled work on paper (c.1968) by Alma Woodsey Thomas (American, 1891–1978)—that reflect the Museum’s ongoing efforts to improve its representation of women artists. Nearly half the works are on view at MoMA for the first time. Making Space is organized by Starr Figura, Curator, Department of Drawings and Prints, and Sarah Meister, Curator, Department of Photography, with Hillary Reder, Curatorial Assistant, Department of Drawings and Prints.

| In the decades after World War II, societal shifts made it possible for larger numbers of women than ever before to pursue careers as artists. Abstraction dominated artistic practice internationally between 1945 and the late 1960s, as many artists sought a formal language that might transcend national and regional narratives—and for women artists, additionally, those relating to gender. But despite new opportunities, women often found their work dismissed in the male-dominated art world and, without the benefit of Feminist advances that would take root in the 1970s, they had few support networks. |

| The exhibition surveys the contributions that women made to the remarkable range of abstract styles that took hold internationally during the postwar decades. Following a trajectory that is at once loosely chronological and synchronistic, it is organized into five sections: Gestural Abstraction, Geometric Abstraction, Reductive Abstraction, Fiber and Line, and Eccentric Abstraction. Building on the legacies of modernism in the early 20th century, artists—in a period marked by recent trauma, migration, and reconstruction—found new urgency for their abstract impulses, whether in the form of existential gestures, the rationalizing order of geometry, or the disruptive potential of new materials and processes. The history traced here begins in the 1940s and 1950s, with several women who attempted to make space for themselves in the domains of painting and sculpture, as well as others who pursued independent visions through photography or works on paper. It culminates in the 1960s, with avant-garde works forged out of the traditions of weaving and craft (disciplines that had historically welcomed women), as well as new types of unorthodox objects whose very nature challenged art historical conventions and boundaries. |

| Gestural Abstraction |

|

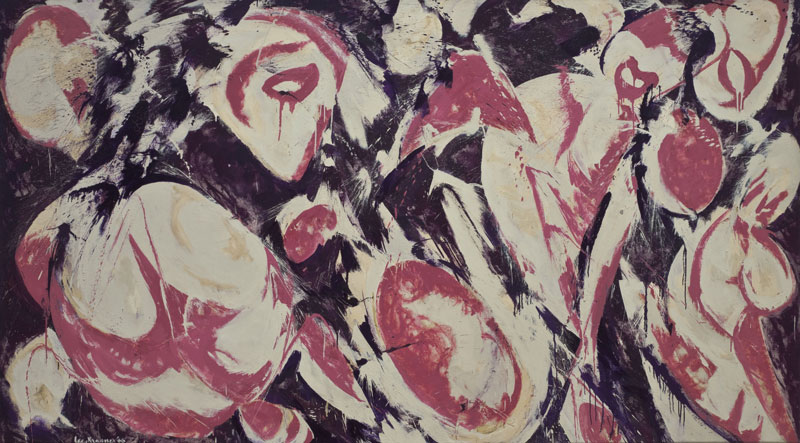

| Lee Krasner (American, 1908–1984). Gaea. 1966. Oil on canvas, 69? x 10' 5 1/2? (175.3 x 318.8 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Kay Sage Tanguy Fund, 1977 © 2017 Pollock-Krasner Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. |

|

In the postwar climate, women artists’ successes were hard won in the hyper-masculine world of Abstract Expressionism. The Abstract Expressionists’ fervent mark-making came to signify the artists’ existential struggles and, particularly in the case of large-scale paintings, heroic actions. |

| Geometric Abstraction |

|

| Joan Mitchell (American, 1925–1992). Ladybug. 1957. Oil on canvas, 6' 5 7/8? x 9' (197.9 x 274 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Purchase, 1961. © Estate of Joan Mitchell |

|

Constructivist tendencies became increasingly transnational in the postwar period, as the geometric legacy of European Cubism and Constructivism travelled across geographic lines. This approach, based on reason and precision, flourished concurrently and in sharp contrast to the subjective, gestural style of Abstract Expressionism. In Latin America, and particularly in the urban centers of Argentina, Brazil, Uruguay, and Venezuela, a geometric aesthetic was closely linked to postwar projects of national modernization and a utopian vision of rationalism, internationalism, and social progress. Women artists were strikingly prominent and able to make formative contributions within the many progressive artistic circles in Latin America. Among the objects on view in this section are major works by María Freire (Uruguayan, 1917–2015), Gego (Gertrud Goldschmidt, Venezuelan, born Germany. 1912–1994), and Elsa Gramcko (Venezuelan, 1925–1994) that were acquired through the landmark 2016 gift of the Patricia Phelps de Cisneros Collection of modern art from Latin America and are on view for the first time at MoMA. Also on |

|

| Anne Ryan (American, 1889–1954). Collage, 353. 1949. Pasted colored papers, cloth, and string on paper, 7 1/2 x 6 7/8? (19 x 17.5 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Elizabeth McFadden, 197 |

| In an interstitial gallery, the relationship between design and abstraction is explored, with a focus on the pioneering work of women within the fields of design and craft. On view are several examples of mass-produced printed textiles—abstract art that you could literally buy by the yard. Textile designers such as Vera (American, 1909–1993) and Lucienne Day (British, 1917–2010) created boldly colorful graphic patterns that enlivened the subdued architecture of postwar modern interiors. In contrast, the transparent, free-hanging room dividers of Anni Albers (American, born Germany. 1899–1994)—one of the 20th century’s most daring, imaginative, and influential weavers—are the result of her intensive engagement with materials and process. Studio ceramics by Getrud Natzler (American, born Austria. 1908–1971) and Lucie Rie (British, born Austria. 1902–1995), two pioneering potters, reflect the privileging of function, form, and texture over decoration. |

| Reductive Abstraction |

|

A number of artists, working in the late 1950s and early 1960s, reacted against the emotionally charged gestures of Abstract Expressionism. Their minimalist works feature flat, uninflected surfaces and highly simplified, mathematically regular forms, often based on a grid. Along with dozens of men whose work was heralded under the umbrella of Minimalism, there were a few key women, including Jo Baer (American, born 1929), Agnes Martin (American, born Canada. 1912–2004), and Anne Truitt (American 1921–2004), who pursued their uncompromising visions at a certain distance from the mainstream of the movement. |

| Fiber and Line |

|

Reclaiming the historical coding of textiles as “women’s work,” the artists featured in this section created radical woven forms that upend traditional boundaries between art and craft. Hanging from the ceiling are monumental weavings by Magdalena Abakanowicz (Polish, born 1930) and Lenore Tawney (American, 1907–2007), as well as Asawa’s untitled looped-wire sculpture (c. 1955). Tawney, along with Abakanowicz and Sheila Hicks (American, born 1934), who is represented by a major wall hanging, was an early pioneer of a new genre known as fiber art, in which artists made soft sculptures by crocheting, knotting, looping, weaving, and twisting fibers, both synthetic and natural. This tendency is also evident in the work of other artists who were experimenting with materials and techniques, such as Mira Schendel (Brazilian, born Switzerland. 1919–1988), represented here with an untitled work, from the series Droguinhas (Little Nothings) (c. 1964–66), made of knotted paper. Like their minimalist contemporaries, artists working with fiber exploited the gridded structure of warp and weft—a logic that is also reflected in a large group of drawings and prints featuring gridded, woven, or lace-like lines by artists including Asawa, Gego, Pape, and Barbara Chase-Riboud (American, born 1939). |

| Eccentric Abstraction |

|

| Carol Rama (Italian, 1918–2015). Schizzano via. 1967. Ink, gouache, shellac, and plastic doll eyes on paper, 24 x 19 1/2? (61 x 49.5 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Dean Valentine and Amy Adelson, 2012 |

|

In the 1960s, women artists were among the key pioneers of a new direction for abstraction that emphasized unusual materials and processes. This new tendency was first identified by the critic and art historian Lucy Lippard, who organized the 1966 exhibition Eccentric Abstraction for New York's Fischbach Gallery. Two of the artists in this section, Louise Bourgeois and Eva Hesse (American, born Germany. 1936–1970), were included in that exhibition. Others on view here, including Lynda Benglis (American, born 1941), Lee Bontecou (American, born 1931), Carol Rama (Italian, 1918–2015), and Alina Szapocznikow (Polish, 1926–1973), created similarly tactile works that suggest bodily forms or functions. Their objects call attention—sometimes loudly, as in an untitled motorized work (c. 1967, from the series Histéricas) by Felizia Bursztyn (Colombian, 1933–1982) that shudders with frenetic motion—to the materials and processes they used. Employing found, sometimes abject objects and raw or viscous matter, these artists injected subversive and obliquely feminist content into the rhetoric of aesthetic purity that had been one of the defining threads of postwar modernism and abstraction. |