ROBERT MOTHERWELL

Elegies, Gestures and Opens

Continuing through April 21, 2012

LESLIE SACKS FINE ART

Brentwood

11640 San Vicente Blvd.

Los Angeles, CA 90049

United States

www.lesliesacks.com

lesliesacksfineart[at]gmail.com

|

This film has an interesting backstory. Filmmaker Eric Minh Swenson had finished shooting his footage of the gallery's Motherwell show, and the next day composer Brett Banducci, who had never visited the gallery before, came in to view the exhibition. In conversation with Brett it came to light that he'd composed a piece, The Basque Suites, based on the work of Robert Motherwell. Well, this was quite an instance of serendipity, synchronicity or however one would prefer to refer to such excellent timing. And so, it was agreed shortly thereafter that Eric would sync his footage with Brett's Basque Suites to complete this short film, Robert Motherwell: Elegies, Gestures and Opens. The thread connecting the work of Motherwell with Spain, in particular the Elegy images, was the painter's emotional connection with the Spanish Civil War, most specifically his humanitarian and anti-fascist feelings. In this regard Motherwell and Hemingway were of one mind, and for both Americans the bullfight was a metaphor for the conflict in Spain: a sacrificial ceremony wherein the power and vitality of the matador and the bull, are pitted against each other in a life and death contest whose victor wins dominion over that which would oppress and destroy them. This kind of romantic conflict is inherently tragic, as were the deaths of 700,000 people in the Spanish Civil War, most of whom were freedom fighters and civilians. |

|

|

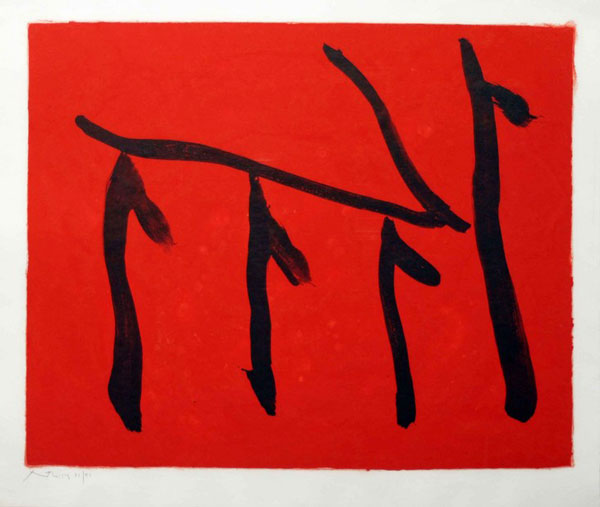

Robert Motherwell(1915-1991) Rite of Passage II, 1979-80 Courtesy LESLIE SACKS FINE ART |

| This metaphor may be barbaric to many of us, but in relation to the carnage of two world wars in addition to the Spanish Civil War, the bullfight had a place in the psyche of many mid-20th century writers and artists, including Picasso who prominently included an image of a bull in Guernica, which was painted specifically to protest the bombing of the town of Guernica in the Basque region of Spain. However, Motherwell brought a transcendental perspective from which to see mortality, and this was the essence of his Zen infused Gestures, which married Buddhism and its lack of attachment to worldly affairs with the passionate gestures of love. Indeed, Motherwell meant the Gestures as an affirmation and exclamation: Je t'aime! The Opens may be said to symbolize the purely unattached mind of the observer - maker of art and practitioner of Zen - a mind open to the subtle resonance of the relative proportions of rectangles; a mind free from the passions that cloud one's reason as symbolized by geometry. To as great an extent as any writer or artist could have succeeded in doing so, Robert Motherwell embraced the staggering ironies of "civilization" in the 20th century, and expressed the value of freedom from both American and internationalist perspectives, thereby anticipating the very situation that exists for artists today in the context of an increasingly global culture wherein freedom and the right to pursue a peaceful existence are still not universal. Despite this, artists dream of what could be, and in so doing make it so. Composers show up at art galleries at just the right moment to collaborate with filmmakers documenting exhibitions of works made long ago by deceased artists whose images transcend the seemingly immutable limitations of time and space. Lee Spiro, Director |

|

|

Robert Motherwell(1915-1991) In White with Green Stripe, 1987 Courtesy LESLIE SACKS FINE ART |

Robert Motherwell (1915-1991) |

|

In 1940, a young painter named Robert Motherwell came to New York City and joined a group of artists — including Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, Mark Rothko and Franz Kline — who set out to change the face of American painting. These painters renounced the prevalent American style, believing its realism depicted only the surface of American life. Their interest was in exploring the deeper sense of reality beyond the recognizable image. Influenced by the Surrealists, many of whom had emigrated from Europe to New York, the Abstract Expressionists sought to create essential images that revealed emotional truth and authenticity of feeling. Robert Motherwell was the youngest and most prolific of the group. Born in Aberdeen, Washington, in 1915, Motherwell first hoped to be a philosopher. His studies at Stanford and Harvard brought him into contact with the great American philosopher Alfred North Whitehead, who first challenged him with the notion of abstraction. What he took from Whitehead was the sense that abstraction was the process of peeling away the inessential and presenting the necessary. After moving to New York and becoming acquainted with a number of artists, Motherwell recognized in them similar desires. Living in Greenwich Village, he became part of an exciting group of young artists. Forming a community and living on what little they had, the Abstract Expressionists made daring experiments in painting and in the intellectual investigations surrounding it. Their break with the traditional art conventions often provoked the harshest criticism from the establishment. Despite this, these early years were an incredibly productive period for Motherwell—seeing him experiment in a range of media, from painting to collage. His work often expressed the actions of the artist through dramatic and bright brush strokes. Valued for their energetic imagery, they attempted a pure emotional response made real in paint. His collage also concerned itself with an awareness of the presence of the artist in a work. Using torn paper on minimalist backgrounds, he created work that was at once discordant and lyrical. Beyond his individual efforts as an artist, Motherwell played a major role in the intellectual and artistic development of the underground New York art world of the time. Reflecting on those early years, he spoke of their belief that “if the abstraction, the violence, the humanity was valid in Abstract Expressionism, then it cut out the ground from every other kind of painting.” It was this revolutionary sensibility that determined both his life and his art. This work, however, grew not simply from a desire to present a new American art form, but a need to express the major human themes in paint. Like the great masters, Motherwell’s importance can be seen in his attempts at expressing something monumental. With the advent of Pop Art and its concentration on popular culture themes, the art public began to long for the idealism of the Abstract Expressionists. In relation to Andy Warhol’s soup cans, Motherwell’s large abstract paintings began to achieve a majesty in the public eye. Motherwell’s politics and spirituality were welcome reminders of a time when one could make art that did not engage the cynicism of a post-modern era. No longer the black sheep of the art world, Motherwell began to enjoy the fruits of years of dedicated work. It seemed, however, for many of the Abstract Expressionists that the newly found appreciation could not counteract the turbulence of those early years—many dying young or taking their own lives. Though somewhat alone, Motherwell committed himself to producing highly experimental work of emotional depth for the rest of his life. On July 16, 1991, at the age of 76 he died: the last of the great Abstract Expressionists. |